Things may have gotten too serious too quickly, but I gather up the long skirt of my dress and step out of Steve’s vintage yellow bug—a car I’ve dreamed of owning since I was little— one of Steve’s many green flags. Maybe, like you always said, despite the father who abandoned me and a failed marriage, I believe in the magic of happily-ever-afters. I tell myself it’s carsickness making my stomach turn, the pickle and peanut butter toast I wolfed down for breakfast or maybe Steve proving his love by showing up dressed in a tux and his black Converse when I dared him—another green flag—but deep down, I’m pretty sure it’s something more serious. You always say it’s easiest to come clean early, but I can’t figure out how to tell him we’re probably gonna need to special order a car seat designed for a bug without you coaching me through it. I try to picture an older, balding Steve sporting a dad bod, but I can’t, so how do I know I’ll love him forever? How can I be sure Steve won’t dump me in this parking lot, leave me to raise a child I wind up resenting like my mother resents me for ruining her life? You’d say, Cycles are meant to be broken, but THE CLOCK IS TICKING, AND IT’S ALMOST TOO LATE!

Steve unlocks the door, so I follow him into the gun shop he inherited a decade ago and think of how his handle, YourSecondHusband, felt like a challenge, which—as you, more than anyone, knows—I’m always up for, so how could I not have swiped right? He looks up at the giant portrait of his mother behind the counter, and in his sexy baritone says, “Mama woulda loved you, Boo. Wish she coulda met you.” Mama’s gunmetal grey eyes bore into me and tell me otherwise, and more than ever, I wish I hadn’t ghosted you three months ago because lunch with Steve felt more important than crying on your couch while you scribbled in your notebook. In my head, my mother tells me, For chrissakes, his mama breastfed him until kindergarten—she’d convince him you’re looking for a meal ticket. You would tell me to ignore my mother’s voice, so I look up at the ceiling and mouth, Fuck you, Rose! And stare Steve’s mama directly in the eyes. But my mouth waters, and I can’t breathe, so I close my eyes like you’d tell me to and list five people who love me: my cat Pooh-Bear, besties Catherine and Ev, Mom’s ghost. And Steve, of course. My fingertips thaw, but my stomach keeps churning. Steve and his tribal tattoo and dirty blond dreads disappear behind the shotgun display just in time to miss me puking into the trash can.

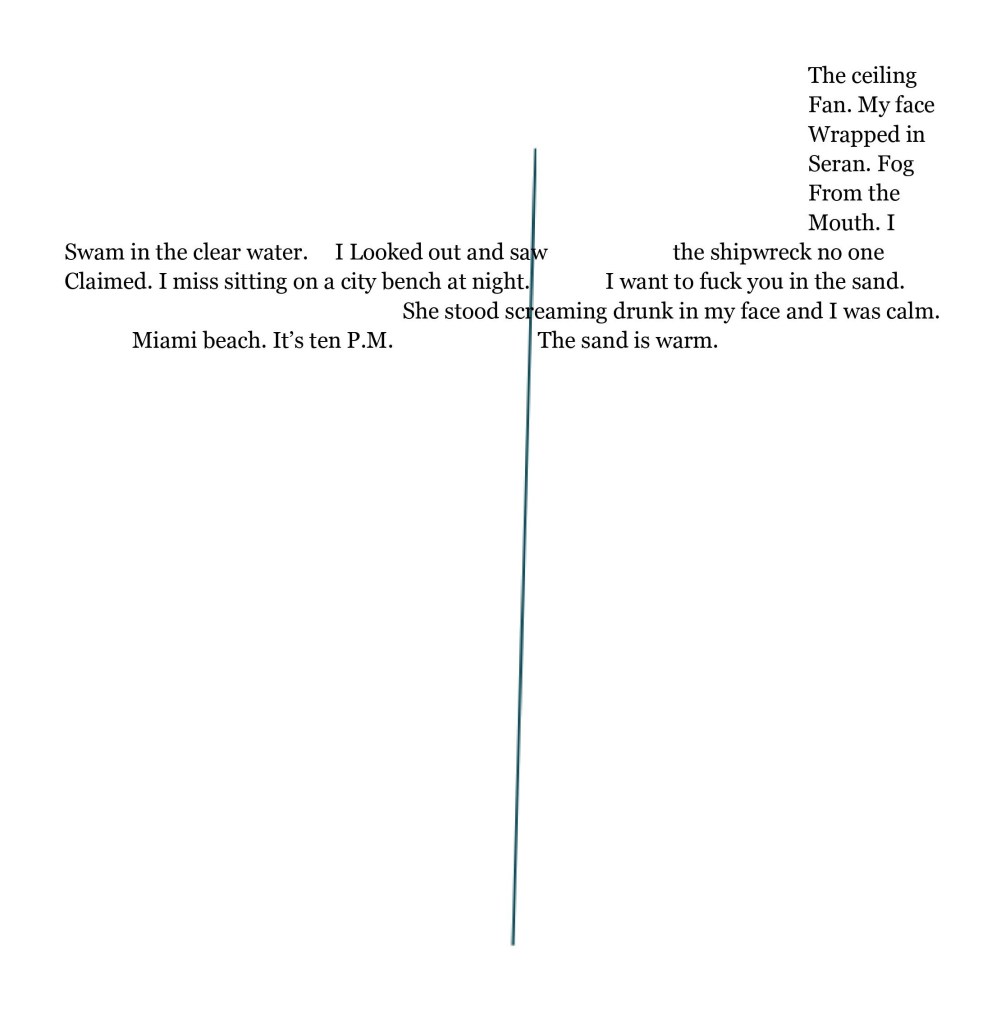

Hands trembling, I take the phone from my purse—you’re the only person who’s been there for me. Even though I paid by the hour, I believe you actually care. I type, Help! Need intervention! Courthouse in 20? Re-read the text and add double prayer hands to show desperation, but I slip the phone into my purse, message unsent.

Steve reappears carrying a small wooden box. His eyes grow moist when he sees me changing the garbage. He takes the soggy trash bag from me and says, “No need to dirty your pretty hands today, Boo-Boo!” I avoid Mama’s eyes, but my cheeks blaze. I know I need to tell Steve. As I open my mouth, my mother pipes up, Fess up under no circumstances–not even gunpoint. Not til he’s put a goddam rock on your finger! She harrumphs and adds, Looks like a runner if you ask me But I’m not asking her anything. I wish I could block her from my thoughts as easily as I did from my life. You applauded my epiphone that I should always do the opposite of what my mother would.

I clear my throat to tell Steve the truth, but he holds a wooden box out to me and says, “Mama woulda wanted you to have this.” A gigantic sapphire sparkles under the fluorescent glow. My heart thuds even though I shouldn’t be surprised to see my favourite gemstone—everything’s lined up since our first date at the Sparrow Café: his flamingo print shorts, the flamingo garter tattooed around my thigh; my hot pink converse, his black. At the counter, I ordered Sparrow’s spiced dragon chai with extra froth, and Steve turned to me with his boyish grin and said, Wild! That’s my order, too! Each time we find more common ground, it’s like Snow White’s little bluebirds are tugging my heart up into the clouds. We both played varsity volleyball before dropping out of art school—him to help with the shop while his mom was dying, and me because I just stopped showing up; we both want at least two kids because we grew up “only and lonely,” and we’re both petrified of small breed dogs, especially white teacup chihuahuas with pointy teeth because they attack like hungry piranhas. In my head, you say, Your avoidant attachment stems from your germaphobe mother withholding touch and intimacy once you started school, and, because you couldn’t trust her, you tend towards insecure attachments, which means I’m getting in my own way because I don’t think I deserve Steve’s love.

Steve takes my trembling hand. The ring easily slips onto my finger and he beams, “A perfect fit!” The sapphire winks up at me.

I shake my head to clear it, fake a smile and say, “Absolutely stunning!” Really, it is. All of this is.

Steve laughs and tucks the ring box into his hot pink cummerbund. When he takes my hand, electricity zings up my arms and into my nether regions. I close my eyes and try to imagine us five years from now. Three kids immediately pop into my mind. My heart races. A two-car garage appears, then me with my mother’s hips, and Steve, dread-free in a button-up and tie because we’re off to church, and there’s probably another cat or non-chihuahua dog keeping Pooh-Bear company inside, and it all feels exactly right, and I realize it’s me who’s afraid and likely not Steve. I point at my still-flat belly and say, “Ready for this shotgun wedding?” He wraps his strong arms around me, and as he twirls me around and around, I thank god I didn’t send the text because I’ve figured this out on my own like you always said I could.

Rachel Laverdiere writes, pots and teaches in her little house on the Canadian prairies. Find her recent Pushcart Prize and Best of the Net nominated prose in Sundog Literary, Lunch Ticket, and Longridge Review. For more, visit www.rachellaverdiere.com or find her on Twitter at @r_laverdiere.