I’d been running the machine for, oh, maybe a dozen years when Ang came in to check for a thing they were suspect of in her chest. “Routine,” I said, to make her feel better. But no one came in just for no reason. We were looking for the one big thing.

And I knew how to find it.

Little woman but the room changed as she walked in. Dark hair long that swayed and suddenly everything seemed brighter. First time in who knows how long I noticed the person before a scan.

She handed me her paperwork and I mumbled toward it, “What music you into? Jazz?”

Better to maintain objectivity.

She shrugged and I turned on some music as she lay in the machine.

“Just hold tight, ‘ll be over soon. Ten minutes max. Depending on how still you stay.”

She nodded.

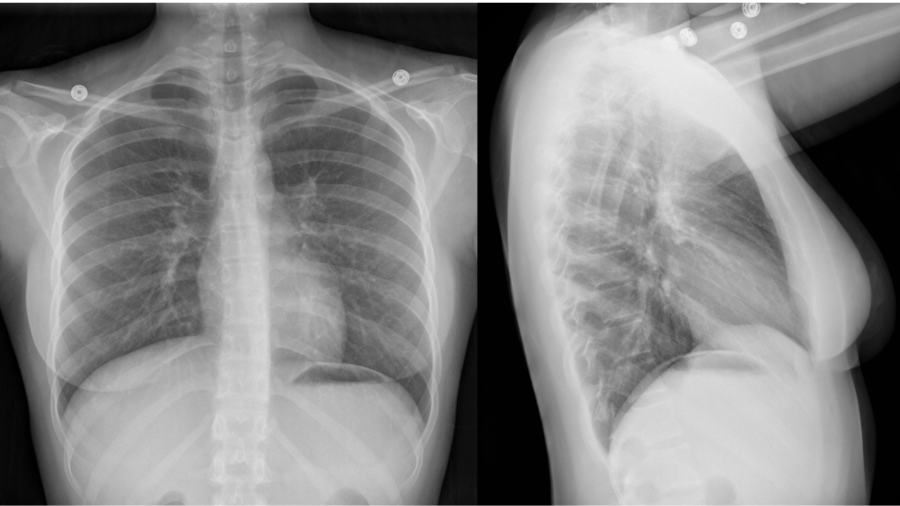

It’s unmistakable to a trained eye, what we’re looking for. Dark masses. Vacuous spots where it looks like a piece of someone is missing.

Thing was, Ang’s body wouldn’t take on the image. Just wouldn’t read right. Even when she stayed still, the whole of her was a blur. Over and within her, an apparition, light, showed on the screen. Three times I tried and the ghost kept dancing, glitching out.

I’d never seen this in an image. My scan, like all the others who had the one big thing, looked like craters on the screen. Conclusive.

“Sorry,” I said through the mic. “A minute.” I ran diagnostics on the machine. All clear.

We’d been instructed not to panic in the case of irregularity. Not to read into it.

And yet.

She winced. “What’s wrong?”

I could feel my voice shake over the machine’s hum. “Let’s try one more time.”

Her face softened and she held her breath. I pressed scan again.

The machine pulsed on. Again, the image everywhere seemed filled with light. No layers of tissue. No grey spaces where the air should fill her lungs. No deep dark craters.

She got dressed. “You see anything?”

I pressed print and handed her the paper: Inconclusive.

I hoped she found the hope in this. She could live a life without the knowing. So beautiful where there are no answers. No name for what you have. Or are.

She looked down at it. “So what now? I just go somewhere else? Try again?”

“Honestly?” I leaned into her. “I’m pretty sure it’ll show up the same way anywhere.”

“So then, what is it?”

I moved closer, closer. I could see something in her eyes then. An extra light. The apparition alive from within her. Like she had a doubled soul.

“What is it they sent you in for?” I said.

“A pain they couldn’t find a why for. I feel it though.” She put her palm on her chest. “Here.”

I reached my hand over, gentle, like touching the surface tension of a pool of pretty waters without making it break. Then, just an inch or so over her skin, there was a spark. A field. An edge to her. A magnetism.

“That,” she said.

She looked into me. Her eyes were backlit like she held a star inside. If it were the one big thing in her, she’d be empty and sinking. I knew that cold gravity. I felt the thing in me pressing against my bones.

But Ang glowed. An extra life in her light. Inconclusive.

“I feel it,” I said. I did.

“Thank you.” She broke and crashed, crying. “I just needed to know it was real.”

If I had more days to give. Weeks to check on her records. If I could give her only this.

“It’s real,” I said. “You’re real.”

Dana Jaye Cadman is a poet, writer, and artist. Her work recently appears or is forthcoming in Conduit Magazine, Four Way Review, The Glacier, Third Coast Magazine, and elsewhere. She is Assistant Professor and Director of Creative Writing at Pace University, Pleasantville. See more at danajaye.com.