Today the milk smells like a barnyard. Grass makes animals taste like animals. Even before her belly swelled, she didn’t want cow in her coffee and now she triple checks the date on the milk carton, counts the days it’s been open on her hand (five). Time has been troublesome since 33 weeks and 4 days ago. She throws the milk away.

*

Moo moo, says the cow in her dream. The cow is her mother 25 years ago at Mt. Kisco Country Club and the moo moo is the long, flowing dress her mother wears because tonight there is a BBQ on the pool’s lawn. They will eat watermelon and roasted pig and corn and the kids will chase fireflies into paper cups while the parents talk and drink bubbles from plastic flutes.

When she awakes, she wonders why her mother called that outfit a moo moo and not what it really could be: a goddess gown.

*

She sits on her leather couch and waits for the lactation consultant. Now, at 40, will her body know what to do? The doorbell rings. As she peels her pink hide from the gray hide, she’s aware of all the flesh around her bones— too much flesh— her diagnoses of pregnant and slightly overweight have creamed together. Even though she can’t see them, she knows the hinds of her legs are now red and stippled.

Knock knock, says Katie the Consultant.

As she takes her breasts out, she remembers: the pool’s dressing room. It smells like chlorine and spray deodorant, sunscreen and grilled cheese. There are milky-white wooden walls. Every day, she leads her trio to the tampons under the bathroom sink. They peel off the paper and stick their fingers through the cardboard, wondering where to put it and who will put it there first.

Then they stand on the rickety bench, peering out the windows into the pool area. There is Matt the Lifeguard, eighteen and blond-haired, blue-eyed, lap-swim-muscled; and then, their mothers, gossiping in lounge chairs. Hers wears tennis whites instead of a bathing suit.

*

She alternates making C’s and U’s with her hand over her size G’s.

It will feel natural, Katie the Consultant is reassuring her. Baby will know what to do.

She is not convinced.

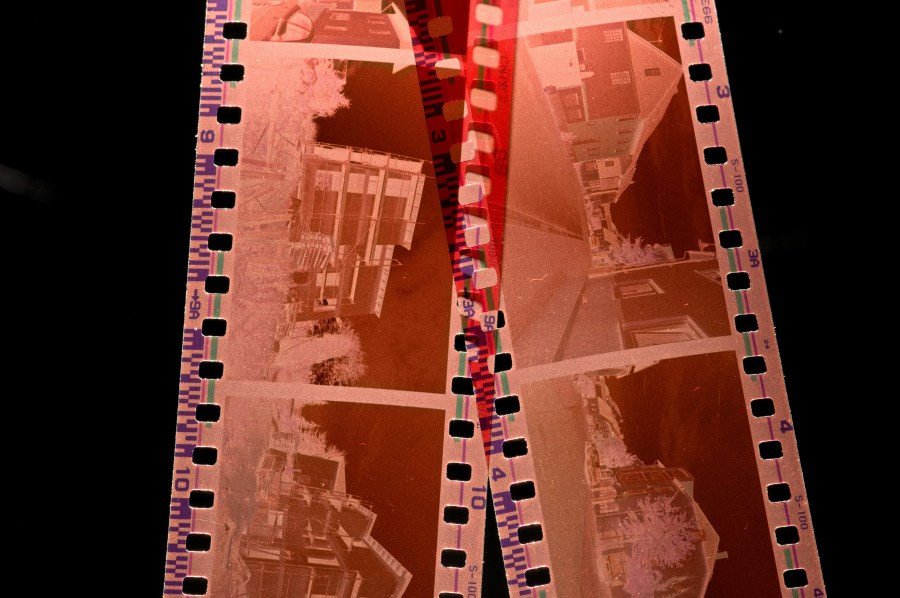

Will baby know this—that she has never known what to do with her breasts? In the last two decades, she’s fought nature, augmenting them into larger, raised shapes, detaching the nipple and then anchoring it into a higher, perkier place. If baby is a piece of her, severed, will it too, fight nature?

She contains acres, wide-open pastures of all the people she’s been. And oh, how that body now stretches, stores, expands. Is it natural then, that she should be so concerned about cramping, contracting, shrinking? She’s more worried about fit: into her bikini, into her child’s gaping little mouth.

*

At the pool, her brother, four years younger, always wiggles around with a woggle between his legs and says things like amaze-balls, tiggle-bitties, and awesome-sauce.

*

Katie has brought a plastic baby doll with flanged lips.

Katie models football hold, where baby feeds wedged under the armpit. She wonders what the little toenails will feel like around her back, if they will flounder or grip or curl.

Don’t worry about the arms or legs. Katie the Consultant reads her mind. Baby is used to being smooshed all together.

No one has prepared her for this type of intimacy.

She’s taken aback at how a newborn, like a vampire or a pet, doesn’t eat; it feeds.

*

Ol’ McDonald had a farm, E, I, E, I, O.

*

Her mother calls from North Carolina after the appointment.

I finally lost weight and wore a bathing suit, her mother is saying. And your dad, you know how he just hates big boobs. Hates ‘em. He just walked by me, raised his eyebrows, and said Barbarella.

*

These are the words about birth her mother and sister swat around: bloody murder, ripped, freaked out, elderly pregnant, ruined, huge.

These are the phrases about motherhood her friend—an acquaintance, really—texts about her newborn, age 42 days: exclusively breastfeed, why am i doing this to myself, husband is useless, cried 3x, brain fog, don’t drive anywhere.

Every text contains a command or a recommendation. You should. Don’t.

Which fears are her own? This unsolicited chatter swarms into her mind and she is once again frightened. She will be: zombie cow.

Why not: divine mother?

*

Her mother refused to change in the pool’s dressing room and her father gladly shelled out for a cabana every season. A windowless 10×10 closet behind the pool’s entrance. One afternoon, a storm rolls through and she and her trio squish inside. Under the thunder, she hears a softer twinkling: laughter, music. She shushes the girls and together they squint through the cabana’s slats.

The teenage lifeguards dance close together. Matt the Lifeguard roams his hands freely over Liz Head Lifeguard’s chest. In front of everyone! No one seems to mind.

Something inside her shifts and she nervously jams the V of her toes into her Achilles’ heel.

The music is low but the lyrics are unmistakable.

Bwok, bwok, chicken, chicken. Bwok, bwok, chicken heads.

The words travel from the cluttered, musty lifeguard shack, through the sliding window, and out into the green, impressionable world.

*

Her mother arrives with a can of formula, just in case.

She doesn’t know that, in those first dark days after baby is born, her breasts will work on an invisible clock that no one, not even Katie, told her about. It will disgust her. She will leak and spurt milk from bedroom to kitchen and her daughter — no longer the anonymous baby— won’t latch and will scream for hours, days, and what seems like years.

Tiggle-bitties. Big ol’ titties.

Her mother won’t whisper Told you so. She’ll shake the bottle and say See, isn’t this easier?

Ol’ Macdonald had a farm.

The formula will froth. Her daughter will struggle to digest. Time will pass more slowly than those endless summers of girlhood. Together they will pace the kitchen and she will drink cold coffee and track her steps, each one getting her closer and closer back to that body that she never knew what to do with.

She’ll forget what she was called before she was Sandra’s mom.

E, I, E, I, O.

Christine Aletti has an MFA from Sarah Lawrence College. Her work has most recently appeared in Twyckenham Notes and the Saw Palm Review. She lives with her daughter in Florida, for now.