We fall in love with the Creature slowly, a piecemeal process over long years of hard work, and each in our own way. For the Creature’s twentieth birthday, we celebrate at home.

“Mr. Frankenstein,” I yell down the basement steps, lobster claw oven mitts pinching my hips. “Dinner’s ready!”

“Dr. Frankenstein,” he says to me when he comes into the kitchen, first hanging his blood-spattered lab coat on the hook at the top of the stairs. I smile and say I’ll call him doctor when he defends his dissertation.

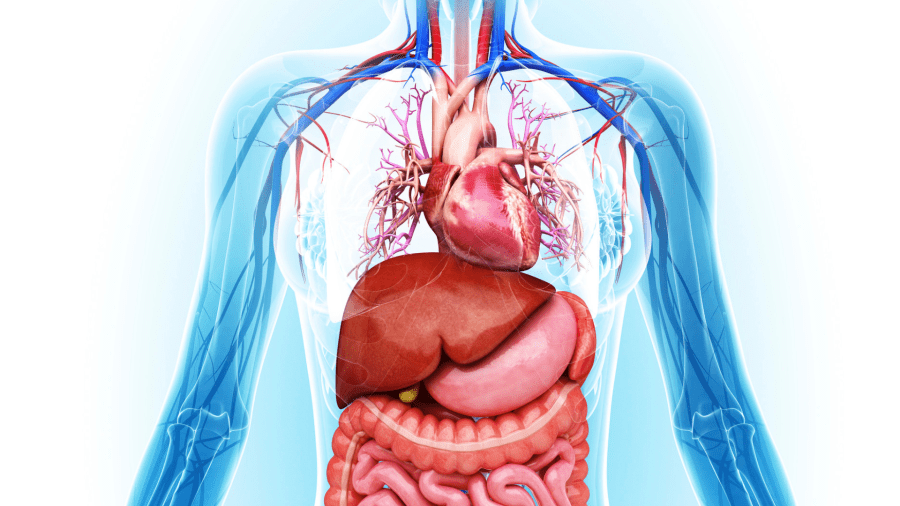

The Creature lumbers up the stairs behind him and moves quickly to the kitchen chair I keep covered in black trash bags for easy clean up. “Hello, handsome,” I say to him, winking, and goodness, look at the Creature: One blue eye, one green, his skin wax white and body a web of silver scars, like a giant palm waiting to be read by gentle fingertips. “And what’s new with you today?”

“Liver,” the Creature says.

I ladle peas onto their plates. I scoop pot roast from the hot pan, the onions oily. I serve my husband the tenderest pieces of beef. I serve the Creature the bits from the side of the pan where the beef has burnt and gone tough. I eat only the vegetables, don’t have the stomach for meat anymore after the bodies we’ve worked through together.

“Old liver was underperforming,” Mr. Frankenstein says, chewing delicately, his teeth sensitive, while the Creature’s massive jaw rips the beef to shreds. Such powerful mastication!

I spear a red potato and tease Mr. Frankenstein, tell him I won’t be going out grave robbing tonight, and he laughs and says quite right, not in this cold and wet weather. I haven’t been grave robbing in years (it’s grueling work, hard on the back), but the occasion of a birthday makes me nostalgic, even silly these days. I find myself playing a younger me, the daring wife who, before Mr. Frankenstein lost his graduate funding, left home after midnight to find the freshest mounds of earth. I scaled wrought iron gates, frightened caretakers with recordings of wolf howls, brought home stomachs wrapped in wax paper, all while Mr. Frankenstein graded another stack of essays.

“Mary,” he’d wept into my bosom, when he could neither finish his work nor give it up. “I’ve let us down, Mary.” But I rubbed his back and promised him he hadn’t failed. That I didn’t care, that even if he did graduate I didn’t want him adjuncting, making no money, always exhausted, never enough. That I understood why he would never be satisfied with the tedious, glorious process of creation.

These days, new livers arrive in a refrigerated van from our friend Mr. Igor at the nearby crematorium. So civilized.

“But since I’m not grave robbing tonight,” I say, “perhaps we could all play a game?” And at this, I pull a package from under the table and hold it out to the Creature. “Happy Birthday!”

The Creature does not care about birthdays. His age is not countable as no part of him is the same age as another. Still, he indulges us. “What is this, then?” he says and rips the brown paper from the present, revealing a vintage game of Operation. The Creature smiles and thanks us both. He is not a Creature who laughs, though he says that he loves how much we both do.

“Sweetheart,” says Mr. Frankenstein to the Creature, taking his hand. “Here’s your real present.” Mr. Frankenstein hands the Creature a cat from a covered basket, a brown and black dappled stray we’ve been feeding for months, who the Creature has begged us to take in.

“We can’t say no to you,” I say. The Creature bends to place his scarred hand low to the floor and holds it still until the cat sniffs and finally nuzzles him. I find myself wiping away a quick tear and when the Creature notices, I huff a laugh. Sensitive, my husband calls me fondly, but I didn’t used to be. Perhaps we were never meant to know so much about our insides, about the fragile, tenacious squish and pump that keep us upright. Now I cannot look at cat or Creature or husband without amazement and worry.

We drink wine and the Creature’s new liver does admirably. We play Operation and Mr. Frankenstein loses again and again until he throws down his tweezers and accuses the Adam’s Apple of being rigged. As always, Mr. Frankenstein and the Creature retire to their bed hours before I do. Mr. Frankenstein works best when the sun is still rising and the Creature is never far from his side, receiving his tune ups without complaint, never asking if they are necessary or simply a way to make Mr. Frankenstein feel young again, covered in blood and full of new ideas.

When it is past midnight and I’ve scrubbed the pot roast pan, put away the man and his plastic organs, I make my way upstairs to my cool room and take off all my clothes and stand in the moonlight. The cat is curled on the bed, watching me with distrust, like she can smell the old graves on me.

“You’re safe,” I tell her, and yawn, sucking life from the quiet air.

Like most young women, I used to hate my body. Used to worry about Mr. Frankenstein and the Creature excising me like an appendix, vestigial to their new love. But now I always sleep naked. Now I know my worth. Now, I rest a hand on my round stomach as it rises and falls, content with the miracle of me, in awe of how impossible it would be to recreate me, to contain this world of mess inside such seamless skin.

Gwen E. Kirby is the author of the debut story collection, SHIT CASSANDRA SAW. Her stories have appeared in Guernica, One Story, Mississippi Review, SmokeLong Quarterly, and elsewhere.