Wendy

Wendy goes to school and becomes a professional. There’s no rationale for why she loves accounting, but she does. It reminds her of when she used to count money for her parents’ business. Each transaction feels exact and explicit, like Wendy.

In her spare time, Wendy likes to cook. She has many recipes that tell her exactly how much sugar for this and show her explicitly what kind of sugar for that. But Wendy never follows a recipe exactly or explicitly. It reminds her of science class in high school. Each measurement feels too exact and too explicit, too much like Wendy’s science teacher, a big-breasted woman with a manly jaw.

Sometimes Wendy wonders what it’s like to have big breasts. She has no big breasts. Her ma has no big breasts. Her ah-ma has no big breasts. Her other ah-ma has slightly bigger breasts but Wendy doesn’t like her or them. One of Wendy’s breasts is slightly bigger than the other and she counts the difference between them, between two, between one and half.

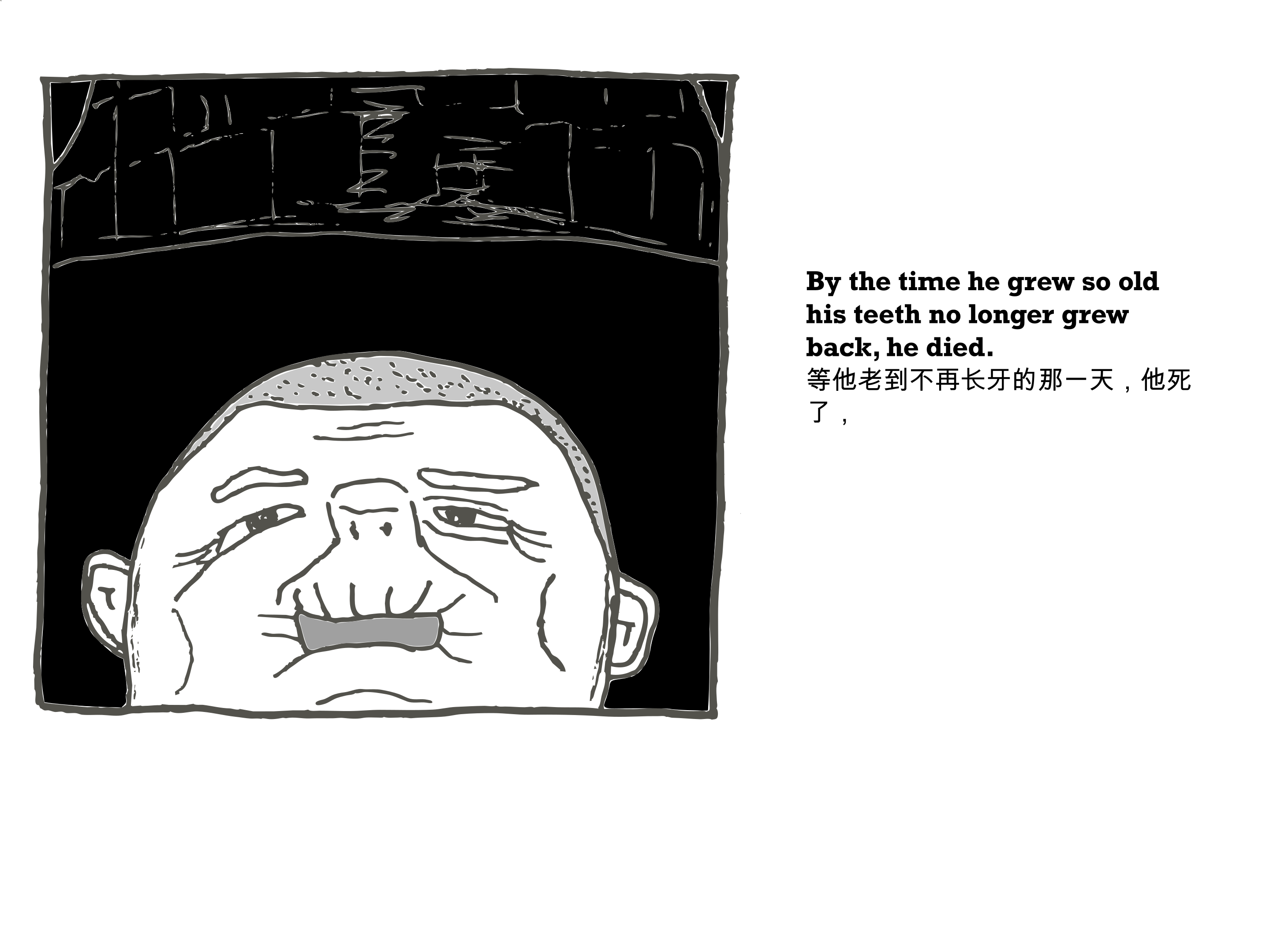

Titanic

My piano student came here on a boat when she was two years old. Maybe that’s why she wants to learn how to play that song from Titanic. She was there and a part of her goes on and on.

Week after week, my piano student talks to me about boys. She places her hands on the keys as she talks, her nails long and polished, her fingers flat like water. She wants me to play for her instead. I don’t know why I give into her purple-shadowed puppy eyes.

Bit by bit, I let my piano student talk me into helping her quit piano. We go rollerblading by her house, her idea of Big Sisters. Her mother shows me how to make Vietnamese spring rolls. Her father asks where I’m from and smiles with half of his mouth that I have no sea in me like his daughter does. That I’m more grounded somehow.

We have our picture taken on the front steps. We are both in shorts and short sleeves. My piano student looks older than sixteen. Her makeup is all wrong, her posture too ladylike. I tell her she doesn’t need all that stuff on her face, but she hands me a Sprite and tells me about getting a job at the music store, about the guy at the music store, goes on about his motorcycle and leather jacket, goes on and on.

Convocation

A classmate asked me out after he came back from teaching English in Asia one summer. He said he had tickets to see the Yankees in town. In truth, I didn’t know what to say. We attended the same lectures and sat near each other from freshman to junior, but we never went anywhere or did anything together. We were the perfect classmates.

So I said I was busy. He didn’t speak to me in senior year and I thought what the hell. When we convocated, he acted like we were strangers even though we sat in the same row under the same alphabet. Even though we used to greet one another with a wave and a smile and exchange notes and glances.

I could’ve really been busy, also, and had to say no. And, honestly, he wouldn’t have asked me out in the first place if he hadn’t gone to Asia and seen so many Asians and come back to the one Asian girl in class.

He was probably destined to marry an Asian girl after that, and that was what he did in the end. When I saw their photos on Facebook years later, a part of me couldn’t help but wonder if that’d be me in the photos instead, had I said yes to the Yankees, and if we’d be a good couple or not. But mostly, I just felt relieved that someone else had said yes to him.

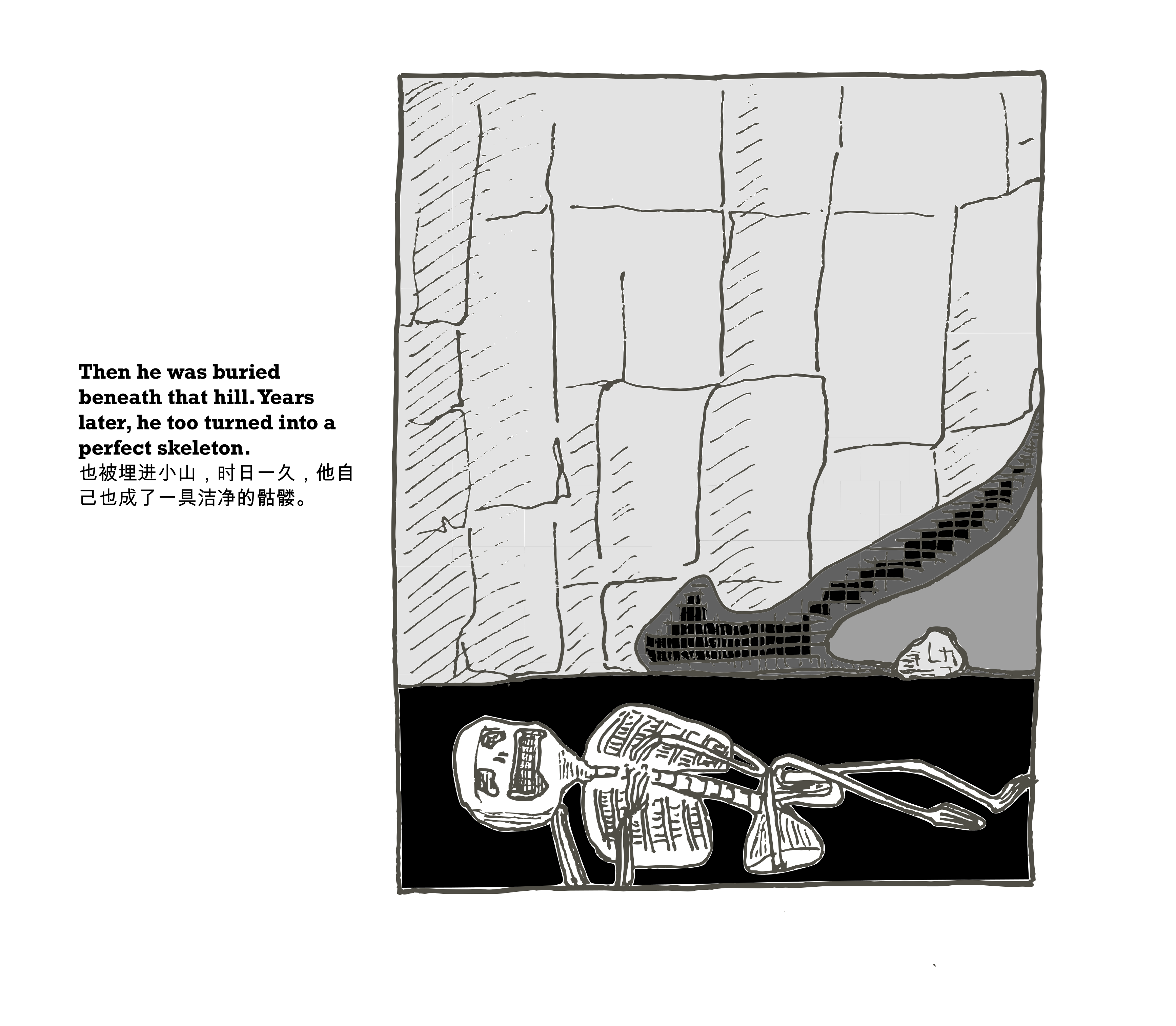

The Cellist

She tightens her bow and flips that fine ponytail of hers that flaps and sways in a Beethoven sonata, the contours of her posture shaped by the cello between her legs, the right one has a habit of making little circles on the floor when crescendo.

Then in limbo, she sticks a pencil in her hair like a meat thermometer and taps the score with the tip of her bow, denting markings of forte, fortissimo, piano, pianissimo, and chanting, bar by bar, tap by tap, Loud, loud, loud, soft, loud, soft, soft, loud, loud.

Once in a while, she pictures someone watching her perform from a distance, listening to her play and admiring how beautifully she plays. He loved her once but she didn’t play the cello then.

Tiffany Hsieh was born in Taiwan and moved to Canada at the age of fourteen. She is the author of the micro chapbook Little Red (Quarter Press) and her work has appeared in The Los Angeles Review, The Malahat Review, Passages North, The Penn Review, Quarter After Eight, and the Best Microfiction anthology among other places. She lives in Kingston, Ontario.