My uncle’s execution is set for two weeks from now, which bothers my mother, not because it’s too soon or that he doesn’t deserve it, but because it’s happening on a Sunday. How could they do it then, she asks as she reads the letter aloud. Is nothing sacred anymore? A part of me is relieved, not that I’d say it—that these years of waiting will finally come to an end. His messy notes from jail, telling us he’s doing fine. Every letter signed with No complaints. My uncle, who once complained about everything, except for what mattered—the rising price of Menthols, the inconvenience of work. How few hairs he had left on his head. Always focused on himself, as if, when he looked out at the vast expanse of the world around him, all he saw was his own unshaven face.

A thing like that’ll get you killed, we warned.

But God forbid he’d ever listen.

My mother believes in justice, even if that means her own brother must go. We all have to make sacrifices—like families at war, who ration their food. Except for us, the war’s amongst ourselves. Either you work to save the planet, or you’re complicit in its demise.

By now, there’s no room for anything in-between.

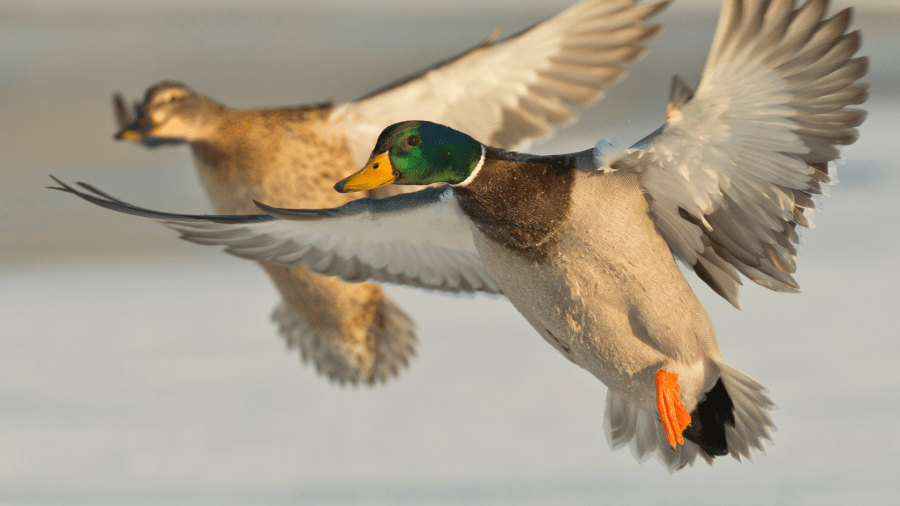

I help my mother pack, since the execution’s scheduled for a glacier in Antarctica. Most of them are held there. It’s easy to ignore and no one takes blame for what happens–even knowing what we know now. The executed simply stand along the edge and wait for the glacier to melt. We board the boat with my uncle, his hands tied behind him, his hair neatly combed but thin. He is older than I remembered. More tired and bothered than his letters would suggest. I wonder if it matters to him that I’m here. If he is comforted by our presence or would prefer that no one saw. It takes four days to reach our destination. We eat with him and discuss whatever we like. I learn about his latest obsessions: his love of animals with giant teeth and TV shows from his parents’ time. I remind myself he’s part of the problem. But his eyes brighten when he speaks, two shining moons as the sun sets in the sea. I feel their warmth, his glow, when he smiles. With a spoon, my mother feeds him his favorite foods from childhood: chicken nuggets and mac and cheese and fruit loops in the morning. He is generous with his meals, insisting that I eat some. When he asks us where we’re going, we say, we are taking you to a glacier. Where you will watch the horizon for as long as you can before the ice gives way and the ocean swallows you whole. He laughs at this a little. He wonders if the earth has a belly and if it’s bigger than his own. I smile at this, until I don’t.

We try to prepare him for what’s to come. My mother bows her head and prays, as he peeks at her with one eye open. He loves when my mother says “mercy.” The sound of it on his tongue, as he echoes her prayer: Mercy for his sins. Mercy for what he must not understand. His hands are tied so instead of reaching for my mother, he leans his head on her shoulder, then mine. I press my ear to his, try to hear inside his mind. To know how a man at the end might feel. But it is quiet inside and empty, uncaring, unlike his eyes. I want him to know that I see him—not only now, but as the man I remember, chasing me through the backyard. When he paused to pick a flower and blew on the seeds so they scattered. He was a child in an aging world.

Complacency, we knew, was the enemy.

On the Sunday we were promised, my uncle steps onto the glacier, smiling as he’s told to move closer to the edge. We stand where the ice is solid, knowing it will melt soon enough—that where we are now will be forty feet of nothingness before the frosty, swirling sea. I imagine myself suspended, witness to this place but not a part of it. Two others move beside him, as they study the faint pink glow on the horizon. I wonder if they’re guilty of the same shared crime—of doing too little, too late, to help. To help what? This, I guess, as we stand there. My uncle chants, Mercy, again and again and again. My mother watches him, unmoved. The man who steered the ship clears his throat: It didn’t have to be this way, he says. I watch as my uncle aligns himself, the back of his hair tousled by the wind. He holds his shoulders straight, as if waiting for a command, but I want him to turn, to run, to get back on the boat and drive. To say to hell with it all, you can take my place in the sea.

But he waits as the captain follows his eyes to the skyline. It is dim, no longer pink, and only then, I promise myself not to look away.

Matt Barrett holds an MFA in Fiction from UNC-Greensboro, and his stories have appeared or are forthcoming in The Threepenny Review, The Sun Magazine, West Branch, TriQuarterly, The Cincinnati Review’s miCRo Series, Best Microfiction, and Best Small Fictions, among others. He teaches creative writing at Gettysburg College and is working on a novel.