We date for three months before I agree to go the farm to meet his family. I hesitate because he calls his parents by their first names. He says, “Grey and Judy want to meet you.”

I agree because he cooks for me. Well, dehydrates. Elijah dehydrates vegetables, presses and pulverizes until they almost pass for pasta.

* * *

We arrive at their front door after noon. The air is warm and thick with precipitation. He rings the bell then kicks the door. A teenaged boy wearing a bandana and muslin shorts answers.

“Judy is counting the seconds,” the boy says.

“Blame it on her—she got her period on the way here and had to stop. Twice.”

Elijah moves through the door. My face pinks in embarrassment.

“You’re Amelia?”

“Yes.” I try to collect myself.

“My brother calls you?”

“Lemon.”

“Bo,” he says. He reaches, takes my overnight bag from my hand. “Don’t call me Bowie.”

“Okay.” I follow them through the hall to the living room.

Elijah calls, “Ready?” And throws open the double doors to the farm.

An enormous tent flanks the house, looms over their garden. Grey and Judy lounge at a cast iron table at its center. On the table, a tea set stands on a large, handcrafted wooden tray. They’re each beautiful. Serene. Butterflies land and launch from Judy’s hair. Grey’s face is lined from effort and intellect. I believe he seduced many women in his heyday.

Judy rises and rushes to us. She puts her palms at his face. Squeezes.

“The prodigal son,” she says. His eyes drift to me.

“Lem.” He says, still in her grasp, “This is Judy.”

Her hands drop. She turns to me. “Amelia. I understand I have you to thank for the visit.”

“I can’t take credit,” I say. Her glance moves to Grey. He stands to greet me, turns first to his son.

“I thought we agreed you’d call when you got close.”

“No, sir,” he says. “You agreed.”

Bo appears again at the door to the house. “I’m ready.” Grey turns again to me.

“I think it’s time we all ate.”

Judy produces a plate of leaves I’ve never seen. No one moves to touch or eat them right away.

“We hear you’re a poet.” Grey says to me. Bo watches hungrily, as if preparing for a hunt.

Judy rearranges the leaves into geometric patterns. The plate takes new life with each configuration.

“She writes hybrid forms,” Elijah corrects. I grab his leg.

“Oh. What about?” Grey asks me.

“My tongue,” Elijah says. He laughs. Grey’s eyes move to me.

I let my hand fall from his leg. “I actually just wrote a series about containment.”

“Containment?” Judy’s eyebrows raise.

“Responses to entrapment—the physical, the self, the soul.”

“How interesting,” Grey says.

“Lem likes to examine feelings of suffering at the hands of others,” Elijah adds.

His parents’ gazes slide to me like sighs.

“That’s true,” I say.

Though, I almost hate him now.

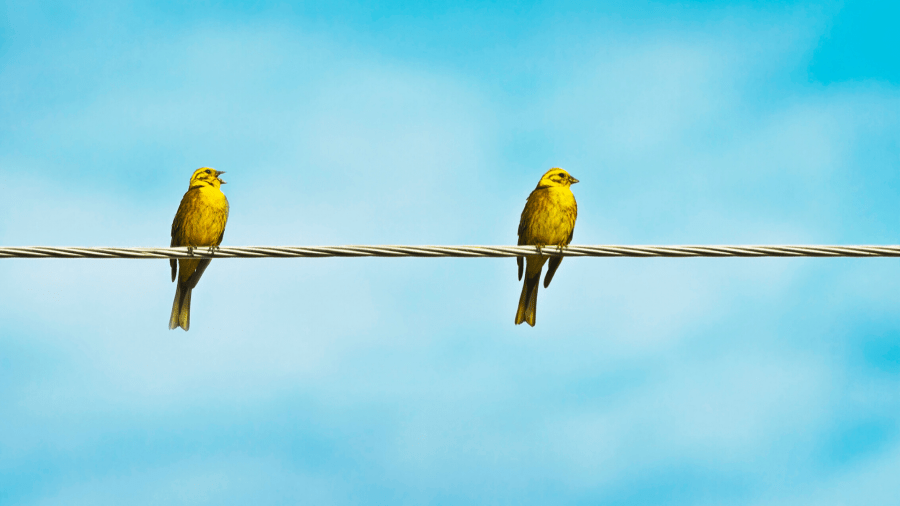

A purple and yellow butterfly—a species I’ve never seen with wings the size of hands—flutters softly to the plate. Lazes on the leaves. Blinks its wings open, closed, open.

Judy puts her fingers to its wings. She works her hand over, carefully, then quickly crumples the wings. She lifts the destroyed life to her mouth. She bites. The purple wings stain the open hole of her mouth as she chews. She closes her eyes. Savors. She wipes her lips with a napkin, smiles, reveals teeth stained the color of a bruise.

Below the table, I grab his hand.

Grey continues, “Have you always wanted to study poetry?”

Another large, yellow-purple butterfly hovers around us. Bo snatches it from the air and rushes it into his mouth. He chews vigorously, crunching and snapping.

“Poetry,” I clear my throat. I watch two more butterflies drop onto the leaves, “always excited me.”

Grey picks up a butterfly by the wing, works it into his mouth. Judy plucks another, pinches its wings between her fingers. The body resists, flails. Then it’s gone.

“You two must be famished,” she says. She holds it to us—to him.

Elijah hesitates. His eyes linger on mine before moving away.

“Mom,” he says.

“It’s one.” She holds it closer. Softens. She whispers, “I know you’ve missed us.”

He looks away from me. Opens his mouth, allows her to press it in. He chews slowly.

I let him go.

“Amelia?” Grey says. “Can we get you anything?”

“No. Thank you,” I say. Butterflies descend and drift towards us from the bushes like music notes. “I’ve brought my own snacks.”

I pull the book from my purse. I tear out the first page. I rip pieces the size of butterfly’s wings. “I’m vegan,” I say.

I lay a piece on my tongue. I can feel the acid of the page dissolving. And I shiver.

Molly Gabriel is a writer and poet from Cleveland, Ohio. Her work has been published or is forthcoming in Jellyfish Review, Hobart, and Barren Magazine. She is the recipient of the Robert Fox Award for Young Writers. She has been selected for flash readings with Bridge Eight Literary Magazine and the Jax by Jax Literary Festival. She lives in Jacksonville, Florida with her husband and toddler. She’s on Twitter at @m_ollygabriel.