The hopeful boyfriend watches in confusion as his partner, the puzzle master’s daughter, excuses herself and walks down the hallway, leaving him alone, on one knee, holding the engagement ring aloft. When she returns to their living room, she carries a lidded wooden box, nine inches in length, which she offers in lieu of a yes or no.

She tells him that he must pass a test in order to earn her hand. The hopeful boyfriend rises; his knees crack as he straightens. He stuffs the ring into his hip pocket, takes the box from her, and asks if she is serious. After all, they have lived together for three years. They purchased furniture and a television together. Earlier this evening, they shared a romantic dinner of chicken marsala, the final notes of which still cling to the air. Surely she must know whether or not she wants to be his companion in marriage. But she says the box is a family tradition dating back generations, and that her grandparents would roll over in their graves if she did not follow through with the task.

She explains the rules: the box contains a rebus puzzle. When the boyfriend figures out the correct solution, she will gladly be his bride. She assures him the whole affair is merely a formality, and to stave off a potential argument in the near distance, the boyfriend acquiesces. What does it mean that it is a rebus puzzle? The hopeful boyfriend isn’t sure, though he refrains from asking.

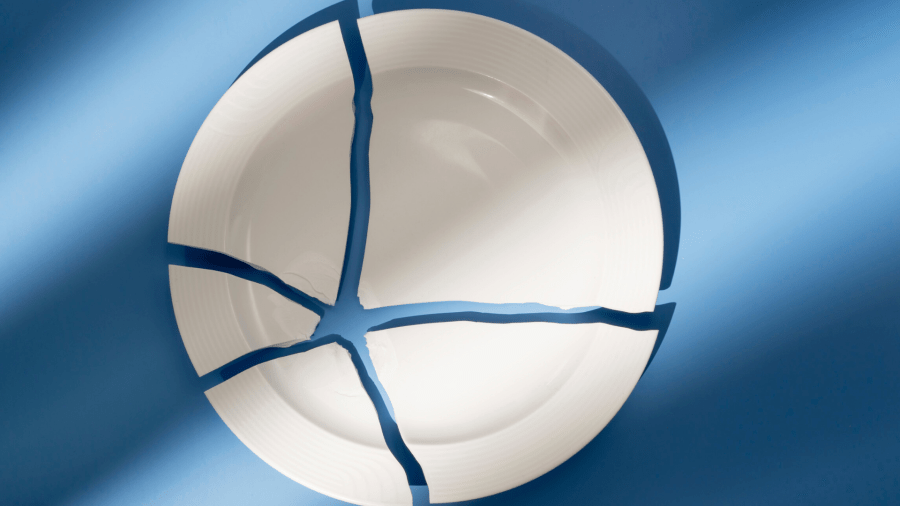

She leads him to the couch. They sit and he places the box on their scratched coffee table. He removes the lid, and inside, the hopeful boyfriend finds four objects: one white square of paper, one ceramic bumble bee, one marble eye, and a black and white photograph of a pair of boat oars. They are all old, weathered by time, the piece of paper more ivory than white, the photograph bent at the corners, and the boyfriend questions if he has seen any of the items before. If these are the original pieces created by her ancestors. But none look familiar. He examines the piece of paper. In faded ink, he reads the words, I hereby leave the following items to my living heirs.

“You know I’m a rookie at puzzles,” he says. “Puzzles are your specialty. That’s why we’re a good couple.”

The hopeful boyfriend stares at the array. He feels around inside the box to see if there’s a hidden compartment. But it’s empty. He returns to the items. Shuffles the arrangement. Tries to stack them atop each other. He clears his throat. Swallows. Hums. After five minutes of contemplation, he can sense an impatience growing in his partner. She sighs when he places the marble to the right of the bee, and she groans when he holds the piece of paper up to the light to inspect it closely.

The hopeful boyfriend wonders if his partner called the puzzle a formality because she assumed he could solve it with ease. Maybe to some the puzzle is simple. Maybe the word “rebus” makes sense to these people. If only he could take out his phone for help, but he’s sure his partner would consider this cheating. The truth is, the hopeful boyfriend hates puzzles. He loves his partner, yet he cannot stand her family’s forte. Moreover, he has lied to her on numerous occasions when asked about word games. After she gifted him one of her father’s books, he leafed through it once before tossing it on the shelf. Whenever she mentions acrostics or cryptics, he nods or lets out a small laugh. He pretends to understand, feigns curiosity, much like his partner responds when he talks about fly-fishing. They love each other despite their different interests. But nodding will not aid him now. He cannot laugh this puzzle into a solution. He reorders the items once more and adds a pensive look to his face. What might her family think if he cannot complete this seemingly simple task? What kind of family forces people to pass tests in order to earn trust? He can understand adapting to traditions, sure. Splitting holidays. Tolerating birthday parties and other events. But a test? The hopeful boyfriend imagines placing his partner in front of his workbench in the basement. “Here, tie a minnow fly,” he’d say. “Tie a minnow fly and then we can get married.”

No, he wouldn’t do such a thing. He wouldn’t make her sweat the way he’s sweating now, the beads forming along his brow. But why is he getting angry at his partner? She is merely following through with tradition. Perhaps she thinks this is pointless, too, despite her being the daughter of a puzzle master. Still, her parents will ask about this moment after they see the ring on her finger, and the hopeful boyfriend knows that his partner is a terrible liar when directly confronted. Her ears heat up and she can’t look you in the eye. He has witnessed this several times: when he asked her if she liked hiking, when she told him about her sexual history, when she tried to compliment him on a new pair of waders.

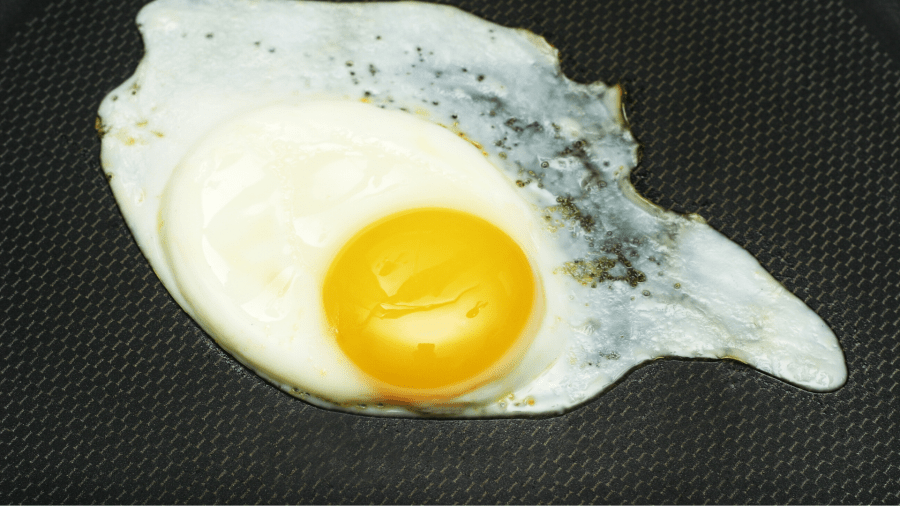

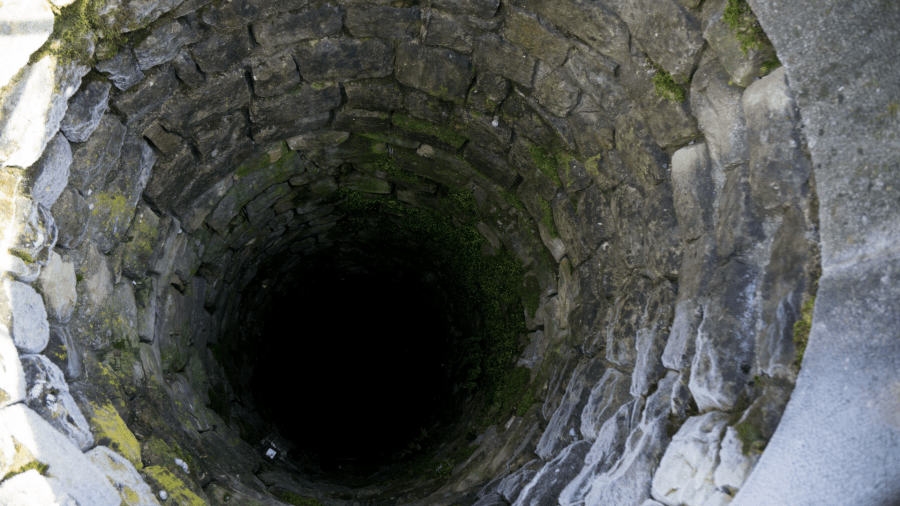

Another ten minutes pass. The hopeful boyfriend holds each piece in his hand, hoping for osmosis to lead the way. The ceramic bee is smooth. It feels nice in his palm, but he gains no insight while rubbing it along his fingers. The hopeful boyfriend remembers the saying “If you give a thousand monkeys a thousand typewriters, they will eventually write Shakespeare.” There is a finite number of possibilities in front of him, and if he keeps track of his attempts, he will solve the puzzle in due time. But it is now past their usual bedtime, and he can tell by his partner’s audible yawns that she is tired. She stands to stretch and quietly paces the room. Then, at the twenty-five minute mark, she finally tells him he doesn’t have to solve the puzzle. It’s just a silly tradition, anyway. It really is nothing compared to their love, which is all that should matter at this moment. She sits next to the hopeful boyfriend and arranges the four objects in the correct order: marble eye, paper, ceramic bee, photograph. Pointing at each, she says, “I. Will. Be. Yours.” The answer is so obvious that the hopeful boyfriend feels immediate shame in his lack of imagination and logic.

His partner scoops the pieces and drops them in the box. She leaves the room, most likely to return the box to its secret chamber, and the hopeful boyfriend stares at the now bare coffee table. The pressure over, he looks up the word “rebus” on his phone. He sees an alternative term, “pictogram,” which to him makes much more sense. Why use “rebus,” which sounds like a name, when you could use “pictogram,” which essentially describes the puzzle’s objective? He remains in this position, staring at the screen in his hand, until he hears the sound of his partner brushing her teeth in the bathroom. He joins her, and when they finish, they change into pajamas, lock the front door, kill the lights, and retire to bed. His partner kisses him. “I love you,” she says.

“I love you, too,” the hopeful boyfriend answers, forever in the dark.

Benjamin Woodard is Editor in Chief at Atlas and Alice. His recent fiction has appeared in, or is forthcoming from, Joyland, SmokeLong Quarterly, F(r)iction, and others. Find him online at benjaminjwoodard.com or @woodardwriter.