My mother died of a massive stroke, but she swears she didn’t. Dropped down dead right there at the breakfast buffet, then climbed back up to her feet—pardon me, she said to the coveralled man behind her—and went on ladling gravy over her biscuits.

It seemed kind of presumptuous to no-thank-you dying, bald-faced rude like a lingering party guest. After all, sometimes folks dying at the all-you-can-eat is just supposed to be the natural order of things, and—between you and me—the secret best thing about mamas is that they’re temporary.

By the time we had driven her home from Fancy Rick’s Breakfast Rodeo, her limbs had locked up into a rigor mortis so profound we sat her in the La-Z-Boy and for three days her eyes slid around in their sockets, tracking our comings and goings but never blinking.

Death is like this, though: first soft, then hard, then soft again, but different—mealy, mushy, like the slow rot of a stone fruit, the innards swelling and skin sloughing off and the flesh-fat yellow then brown then black underneath. A more apt description, in fact, I can’t seem to finger than an overripe plum: a bruise where a woman used to be.

You’re dead, Carol-Ann, says her cardiologist—who she swore was a hack, who she once accused of pumping her full of forever-chemicals to keep her just sickly enough to keep needing him but not enough to die—but she turns her chin up at him and gathers her pocketbook up under her elbow. He presses his stethoscope to her chest and waves me over to listen; the stillness between the lobes of her ribs is stark and stunning, a soundproofed room wallpapered in egg-crate foam, and it’s beautiful and horrible both. On the drive home she snuffles out a series of short gasps I take for crying; later, she pores over the Yellow Pages, points a dagger-finger at a few promising options, and despite myself I promise I’ll call and schedule a consult—not a single cardiologist in the county, I’ll report back after, is accepting new patients.

Bobby-Dale’s new girlfriend says it’s kind of romantic, isn’t it, how much she must’ve loved living, hanging on so tight. Heroic, even. Rage against the dying light, and all that.

And Mama, limp-flopping like a Raggedy Ann behind the cordless vacuum says in her parched voice, sandpaper rubbing together, Why thank you, CiCi, how nice of someone to notice, even though just last night she’d rasped that CiCi was a pointless sack of fluids and phlegm with not a thought bobbing around in all that sinew to spare, and I thought she’d sounded just a little jealous.

I consider telling CiCi that it’s actually a haughty refusal to be caught out that courses like sap through the veins that used to ferry blood and lymph across her cells, a kind of stubbornness that stretches deep into the clay like pipsissewa, but instead I chew the inside of my cheek to a pulp; the balance of things is delicate, after all.

Ronda my therapist says, Have you considered she’s gaslighting you? And I sigh and nod but then shrug because of course I have but also what am I going to do? She’s obviously dead but also won’t die and so I get my parking validated by the little Portuguese woman at the front desk and Mama’s waiting in the passenger seat when I climb behind the wheel, dust and ash pooling on my leather seats underneath her naked pelvis, sharp and moon-white in the sun. I almost sneer to At least tidy up after yourself, why don’t you? but instead I pretend I don’t see; instead I say nothing and she says nothing and when we get home I Amazon Prime a dustbuster to keep in the glovebox because this is the sort of thing family does for its own, isn’t it?

For Christmas, I work back-to-backs at the Down-N-Out and take out a personal loan with 33% interest to buy her the Rolls-Royce of caskets, a shiny lacquered thing with pink satin lining and polished brass hardware and a concave pillow to cup her skull: a real swanky place to spend eternity, and cost as much as a mortgage too, which I guess it kind of is. After dinner she lugs it out to the burn pile, price tag still swinging from the handle, and douses it in kerosene, and for a split second I think how easy it would be to tip her over into the bonfire, too, her beef jerky limbs catching like kindling.

Bobby-Dale and Tammy-Rae and me, once enough is enough, sweet-talk Mama into a meeting with Father Johnson at First Harvest, to get his opinion on what it is Jesus and Mary and the whole subcommittee might think about all this, and it’s easy enough getting her there, rubber waders billowing around her waist to keep her soggy snail-trail of putrid something-or-other from soaking the wall-to-wall in God’s living room. For a while she’d been convinced they’d call her a saint, call the Pope, and her face falls when after some discussion the priests decide that she is an abomination and not a miracle. Father Johnson says it’s a sin against God, her refusing to die, but that just makes her dig her heels in all the harder. She spits a dusty wad of coppery scab at their robe-hems and says she’d rather be an abomination than a Catholic anyway, with that attitude and when we sweep her toward the door she shouts over her shoulder that it turns out there’s no God or heaven or point anyway, and sneers wickedly when they hurry off because she knows they know that there’s no one knows better than her.

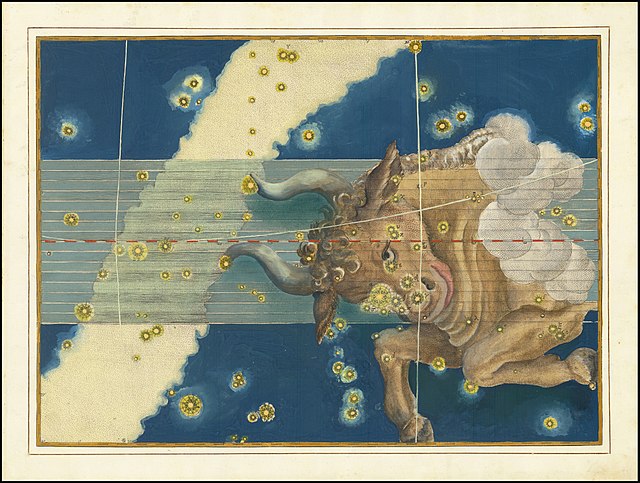

Bobby-Dale takes Mama up to the house—There there, now, Mama, can’t everybody stomach these things is all, like field dressin’ a deer, or the Yankees—and Tammy-Rae and I idle out at the curb and suck down a pack of Marlboros, one at a time. Tammy-Rae wagers this whole business is all on account of Mama’s Taurus sun, Taurus moon, Taurus rising. Trip-Tauruses, that’s about as Taurus as you can get, according to her. I don’t know much about astrology save for what I read in the weekly, but I’ve been driving this Ford Taurus for fourteen years and can’t get the tranny to shift into second to save my life. I figure Mama with stubbornness etched into her bones by the universe itself is like that too: can’t shift.

You’re just like her, y’know, Tammy-Rae says, dustbuster in one hand, cigarette in the other, and I scoff that I was born in June.

No. Long-suffering, I mean. Joan of Arc-type shit. She flicks her ashes onto the floorboard, then vacuums them up.

Leave it, is what I say, this time.

Danielle Barr is a full time stay-at-home mom and sometime-writer. She was the winner of the Driftwood Press annual short story contest, and her works have appeared in The Milk House, The Hooghly Review, Querencia Press, and others. She is currently querying her debut novel. Danielle lives in rural Appalachia with her husband and four young children, and can be found on Instagram @daniellebarrwrites, Twitter @dbarrwrites, and Bluesky @daniellebarrwrites.bsky.social.