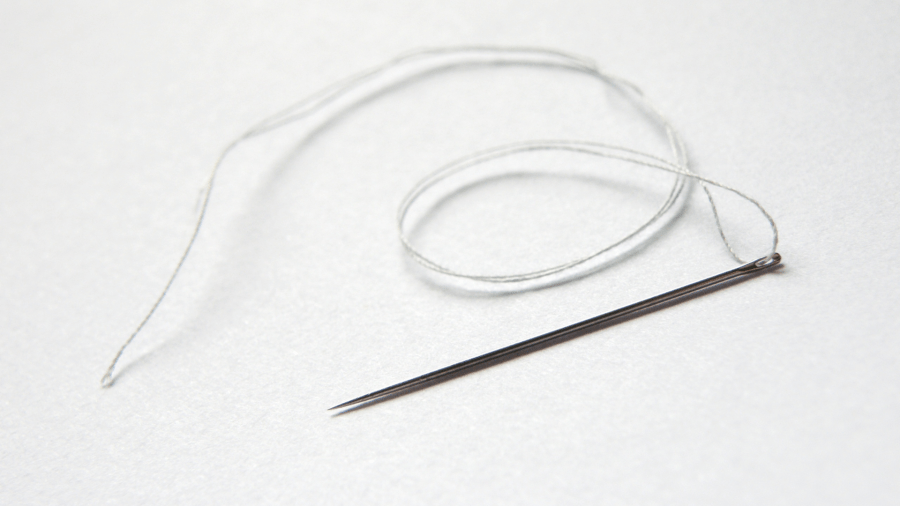

Mary was the first to do it. She used silver thread, and we admired the biblical resonance of her name, her tight straight stitch. She started with the left eye, at the corner away from her nose. It was painful and messy, the needle threading through eyelid, but eventually the blood dried, and there she was in our high school hallways, eyes stitched closed.

After that, it was a new girl every day. You could tell who was new by the crust of red at the stitches, by their bumbling walk and their reaching for every wall.

The boys wrote us off. They said there wasn’t anything political about it. It was just the latest fashion. They opened doors for us, guided us from one classroom to the next. They read our homework aloud and cooked us afternoon snacks: rice with broccoli or macaroni and cheese, whatever they liked to eat.

We had told them about the ways the world worked for us, about our bodies and how they felt always on display, too big or too small, too easy to comment on or whistle at, how some boys didn’t listen when we said no or stop or leave me alone. These boys we told: they ignored us too.

So we no longer watched their football games or returned their smiles from across a room. We stopped shopping at the mall. We wore sweatpants and tee-shirts and never any makeup. The boys said things to us like, You’re really letting yourselves go. And we smiled and noticed the different shades of light that danced upon our eyelids.

We learned to do tasks alone, to take care of our own needs, our own wants. We began to question the need for boys at all. We stopped dating them, began to find pleasure in each other—our bodies smooth and desirous, our laughter light and ringing in our ears.

Eventually, the principal got involved. There were too many girls with too many needs. He persuaded our parents that if our behavior continued, we wouldn’t go to college or find jobs. We wouldn’t get husbands and make babies. Too much thinking, he insisted, is not good for a developing brain.

Our parents agreed. They crept into our rooms at night and ripped out our threads stitch-by-stitch. We protested of course, but slowly, we woke up to see again. Except: there was nothing we could fully recognize from before.

We could see, but it was as if we were seeing for the first time. We saw each other most distinctly. Our limbs and waists and faces. Beautiful, we told the world. And we wanted to look at each other all day. So we did. We looked and looked until Mary took out her needle and thread again. Nobody’s listening to us anyway, she said, and then she stitched her top lip to her bottom lip and we followed, sealing our mouths shut.

Allison Field Bell is originally from northern California, but has spent most of her adult life in the desert. She is a PhD candidate in Prose at the University of Utah, and has an MFA in Fiction from New Mexico State University. Allison’s prose has appeared in SmokeLong Quarterly, DIAGRAM, The Adroit Journal, New Orleans Review, Alaska Quarterly Review, and elsewhere. Her poems have appeared in The Cincinnati Review, Superstition Review, Palette Poetry, and elsewhere. Find her at allisonfieldbell.com.