They asked how many sides the fetus had.

Unsure of what to say, the doctor lied, knowing

they expected the same number as themselves.

When the baby bulged and bounced

down their sides, the sky turned plain and paths

were pathed with flattened fool’s gold.

Like cubes trying to love spheres, they

could only wonder at the failed geometry

of it all – nothing stacking up.

They balanced between the planes

and the points of parenthood, never to under-

stand the trials of being round.

More worried about, than for: they thought

of how schools were unfit for purpose; the streets

bordered by broken fences; the hospitals

confused with their whetted tools. So

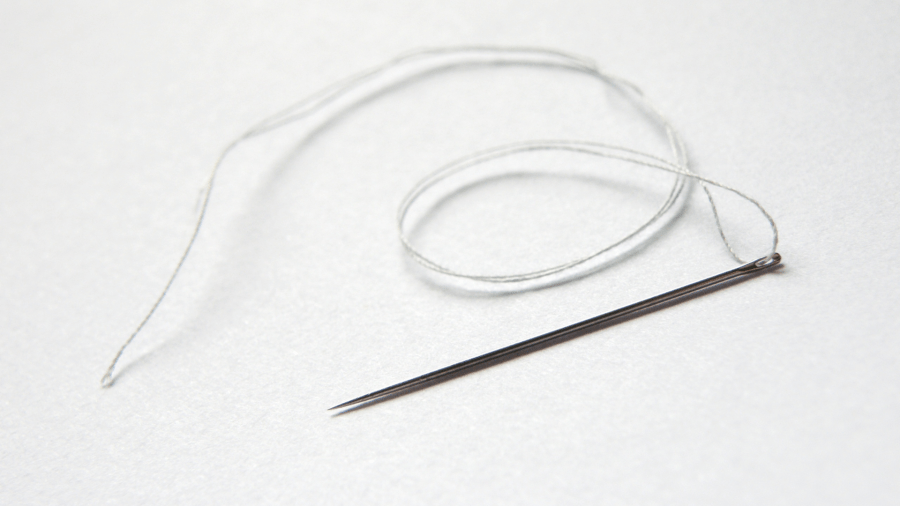

they spent their whole lives shaping their child: a

nip

here, there,

a tuck

a word, just

a word,

a word made of silent letters. And then all

was right-angled in the world; the round peg

chiseled down to fit into a square hole.

Every day, hidden away with tight –clothes–,

straightened |hair| and ironed-out [expectations],

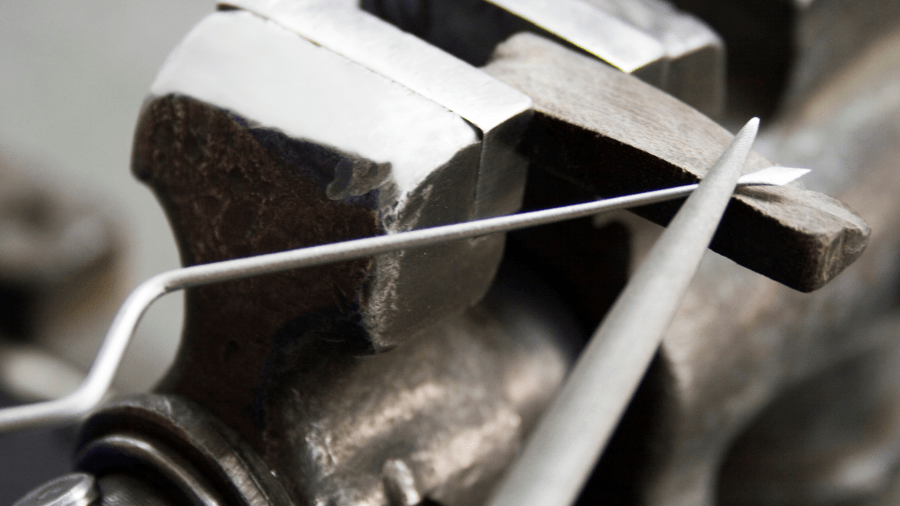

a vised {heart} is by its own (ribs).

Luigi Coppola – www.LinkTr.ee/LuigiCoppola – is a poet, teacher, and avid rum and coke drinker. He has been selected for the Southbank Centre’s New Poets Collective 23/24, Poetry Archive Now Worldview winner’s list, Birdport Prize shortlist, and Poetry Society’s National Poetry Competition longlist. He also performs music as ‘The Only Emperor’ and has a debut poetry collection from Broken Sleep Books due out in 2025.

For music, videos, the writing process of the poem, and other links, please visit: https://linktr.ee/thesharpparentsofaroundchild.