I stole the notebook.

Is this a sentence? I’m looking for hands. Take a stand here.

Yes? Do we all agree?

Anthony, I welcome you to remove your earbud and join us.

Even if your music is off, your extraction of that plastic snail consoles me as a gesture of respect.

Thank you. I stole the notebook. Why is this a sentence? Kylee?

Because it feels complete?

Yes, I just repeated Kylee’s answer in that radically ambivalent way I have of making you uncertain whether I’m validating or questioning it. Bear with me. I’m seeking to destabilize my position in the locus of power. If this feels hypocritical, that’s because it probably is.

What makes the sentence feel complete, Kylee?

There is a subject and verb, though I sense that’s the answer you believe I want rather than a conclusion you’ve reached for yourself. I can work with that. Is a subject and verb enough?

Anthony?

Just stretching. I see. Kaden?

Why did “I” steal the notebook? Thank you for taking this seriously.

No, really, assuming the notebook isn’t invented for the purpose of this lesson, why steal it?

I see your hand, Kylee, but I’d like to give Anthony a chance to answer this. Anthony?

Because.

Very clever. We both win.

Because I stole the notebook. Is that a sentence?

Let’s hear from someone new. I’d cold-call, but I haven’t learned most of your names yet.

You refuse me?

Fine, Kylee, go ahead.

No, because of the because, yes. Because is a subordinating conjunction. Does anyone understand what it means to be made subordinate?

Anyone besides Kylee?

Do you realize you’re experiencing it now?

Yes, Anthony?

It is. It’s always this hot in here because it’s one of the outer circles of hell. No, seriously, if there were windows, I’d open them. That’s why I bought these fans.

Consider this: It is. Is that a sentence?

It is! Excellent.

No, we cannot prop that exterior door.

You are not the first to inform me this classroom is the hottest in the school. Perhaps you could have some compassion. You get to leave when the bell rings. I have to stay.

Quick, bonus challenge! What’s the shortest sentence in English? Kylee?

Nope. Kaden?

I’m? That’s essentially what Kylee said.

Yes, it’s two letters.

Anthony, please close the door and return to your seat. Remember that shooting in Texas? Yes, Texas is far away, but if there’s a shooter here, we want the door to be— I see your point, but we’ll just have to hope the shooter isn’t in the classroom.

No? Oh, you mean as a sentence. No.

You want a hint?

Think.

That’s your hint.

I’ll tell you at the end of class if you haven’t figured it out. Back to the lesson: I stole the notebook. Is the notebook necessary?

Kaden, I see you nodding.

Because you can’t steal something that isn’t there.

Interesting, but not what I wanted you to say. Let’s try another approach.

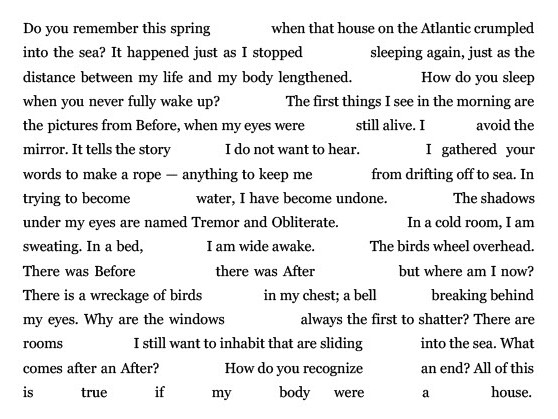

Must you see this notebook to believe it exists, or can I tell you it’s the size of an old-fashioned postcard, that its softbound covers bear a full-color bounty of heirloom vegetables: rosettes of lettuce and bouquets of chard, the veins of each cabbage leaf articulated with aching precision—Anthony, have I even begun to make you care?

Each vegetal specimen is labeled in a font from the last line of a sadist’s eye chart, suggesting the world from which this notebook was stolen is a third the size of our own. A model, perhaps. From “whom” was it stolen? “Who” stole it? How do I know “who” is “who” and “who” is “whom” apart from the fact that “I” stole it?

Simple. It’s a matter of subjects and objects. Who does the action to whom.

Kaden, I feel like I’ve lost you.

Kylee, while I appreciate that you’re either taking notes or working on the bonus challenge, I fear you, too, might be missing my point.

Look. I need your eyes. Here’s a notebook covered with vegetables divorced from any evidence of the dirt that produced them. They resemble eggplant emojis scrawled with Sharpie, but still.

Whose notebook is this?

Yes, Anthony. I stole your notebook to teach you the grammar of agency.

Now, write in your notebooks for the next seven minutes: Tell me what you’ve learned from this object lesson. Specifically, consider the implied “you” in that sentence. Can you imagine yourself as a subject, even when you aren’t on the page?

Anthony, why aren’t you writing?

Sorry, here’s your notebook. Kaden, do you need help?

Go ahead and write those thoughts down. Don’t mind me looking over your shoulder.

Intriguing observation, Kylee, but try to go deeper.

Anthony, why are you putting away your notebook? Please speak up. Wait, I said that door needs to stay—

Well then.

Can anyone put what just happened into a sentence? Kylee?

Hold on, Kylee—why are there so many shuffling papers and slamming books? There’s no reason to pack up.

The bell hasn’t rung! I haven’t given anyone permission to leave! Kaden, come back!

Don’t think I can’t write you all referrals!

Well, Kylee, it’s down to you and me. Believe it or not, I’m on your side. You remind me of me.

Oh. You’re only here for the solution to the bonus challenge?

Everyone else figured it out.

Go.

Jules Fitz Gerald (she/her) grew up on the Outer Banks of North Carolina and now lives in Oregon. She earned an MFA from the University of Pittsburgh and recently attended the Kenyon Review Writers Workshop and Tin House Summer Workshop. Past honors include selection for a Fulbright U.S. Student Grant in Creative Writing and a Lighthouse Works fellowship. Her prose has appeared or is forthcoming in Southern Humanities Review, Fourth Genre, Raleigh Review, Tampa Review, and North Dakota Quarterly. She taught high school English for six years.