Lately I’ve been too busy to visit my grave. To lay on the grass and soak dew into my skin. To whisper sweet nothings down into the dirt where only my skeleton can hear.

Sometimes I think I can see my headstone if I really squint. The other day I swore I spotted it on the horizon, pale green and blinking in midday moonlight, but a car honked on the street and the flat blare wiggled into my abdomen and broke my focus completely.

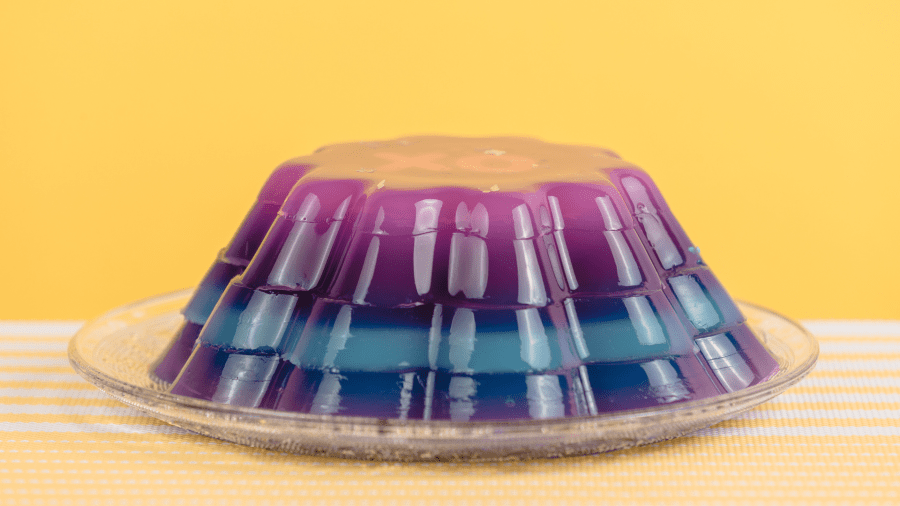

That’s one thing: without a skeleton in my body—a sealed bag of savory Jell-O, really, though no one’s yet noticed—sound moves differently. There’s no sharpness to things. Words wobble in and out of focus. Gunshots start soft and echo around, reverberate themselves into extinction.

But my god, sound is everywhere. Squeaky wheels on a grocery cart make my brain feel like crumpled foil. My daughter’s swim meet is torture.

Not torture. I’m proud of Ari. She’s twelve and still so small but she swims so fast, kicking her little feet up and down the pool until she comes up gasping at the end of the lane, pumps her fist when she realizes she made it back first. Little alien girl, her swim cap and goggles suctioned SMACK to her eye sockets. I couldn’t wear those. I doubt my head would hold its shape.

We’ve been fighting. Before, when she was two and three and a thigh-high hurricane, we didn’t fight. We were best friends who put each other to bed and elbowed each other in the boob by accident during spontaneous hugs and morning snuggles. But she’s gotten mean lately, cliquey with the blonde girls at theater camp and angry for the first time that her dad lives so far away. She told me I was weak the other day, after hearing me argue with him on the phone. She told me he was stronger. She called me spineless. Which, I mean. I am.

So I grounded her. Told her to show me a little goddamned respect. Took away her tablet, drank gin on the couch at midnight, flicking fingers across the unfamiliar apps she’d downloaded: YouTube, Candy Crush, a Barbie something-or-other that made my heart ache from how young it made her seem. An anonymous social media app where she’d said she was eighteen and given our home address to someone named Jarrett.

I let her go to her swim meet. The blonde theater girls don’t swim. Maybe she’ll absorb the other kids’ easy joy and pacifist approach to competition, maybe I have something to learn from their hippie grown-ups with their “COEXIST” bumper stickers and Gentle Parenting. I sit next to them on the bleachers which slowly smush my butt flat and I try to think about something other than the taste of friendly earthworms after heavy rain. Here I am, most of me, showing up.

But the noise. The noise. A thousand kids shouting from the pool deck and their thousand shouts made screams by a thousand whitewashed cinderblocks. I can’t cut through it. The sound seeps into my Jell-O flesh and stays there, leaks through into my brain in a steady roar. Ari is animatedly gesturing in the center of a group of taller kids. I slither off my bench.

I smoke a cigarette at a picnic table outside the rec center. It is dark. The picnic table is wet from rain earlier and smells like the forest it was likely kidnapped from. I put my face down on the table, inhale deeply, and think about my grave. The way the roots of grass lock together and keep my bones for me, in their pile in their box in the dirt miles and miles away.

Low beams of yellow light precede an older model sedan into the parking lot. It pulls up next to the picnic table and idles, driver still sat in silhouette beyond panes of smudgy glass. I watch the figure for a while, flicking my cigarette butt. He’s considering me, too. After a minute, the window rolls down two inches and a very faint voice calls something that I wouldn’t have registered at all if it wasn’t:

“Ari.”

I choke on smoke and my thumb bends backwards—it happens sometimes when I lose control—but I don’t think my shock is visible in the dark. I clear my throat, push smoke out of my lungs, steady my voice.

“Jarrett.”

I walk over and lean on the window. He rolls it all the way down so that I can rest my forearms on the door.

“Hey there, girlie.” His voice is rough and sickening and older than I had thought to fear. “You’re a grown eighteen.”

The cigarette is still burning in my hand. A squiggle of smoke trails into the car.

“Put that out,” he says.

The floodlights come on behind me. The swim meet is ending and families are starting to stream out of the building and into the parking lot. The white light leaves my face in shadow and outlines his features just for me and I reach in without thinking, lit cigarette in hand, and stub the ash in the cool wet of his left eyeball.

He screams. The families behind me turn as one to where I stand beside the unfamiliar car. I don’t look at them. He’s screaming and clawing at his eye and I walk around the side of the building out of the floodlight and disappear.

I text another mom from the swim team. Can Ari come home with you? Everythings fine, will pick her up in an hour.

I lay on the grass, on the shadowed field that sprawls behind the rec center. My nose flattens entirely to my face as I press it into the dirt. I close my eyes. I breathe.

I can feel my skeleton’s presence. She’s safe, I know she is. I’ll be there soon. Promise, baby girl. The soil here is different than at home, a different composition of loam and silt, but I inhale it viciously anyway and fill myself up with the pure base carbon that I am and always was. I soften. I imagine the grate around my plot, the gentle slope of ground above my bones. There’s silence.

Helen Savita Sharma is a librarian and writer working on her first novel from her home in North Carolina, where she lives with her partner and two cats. Helen’s passions outside of writing include “Higher Love” by Steve Winwood, ensemble dramedies, and watery Dunkin’ Donuts iced coffee.

Helen,

Wow….what a vivid, visceral story!!!!? Beautiful!

❤️❤️❤️❤️

LikeLike

Pingback: Short Story Sunday – Coffee and Paneer